Frieze Masters

Overview

Stephen Friedman Gallery is showing a curated presentation of work by Melvin Edwards at Frieze Masters 2015. Comprising a barbed wire installation first conceived in 1970 and here being realised for the first time, it is accompanied by related works on paper from the same period.

Stephen Friedman Gallery is showing a curated presentation of work by Melvin Edwards at Frieze Masters 2015. Comprising a barbed wire installation first conceived in 1970 and here being realised for the first time, it is accompanied by related works on paper from the same period. It forms part of a body of barbed wire works produced by the artist in 1970 for his solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of Art, New York, the museum's first show by an African American sculptor. Edwards' use of industrial materials such as wire and chains evokes complex and menacing narratives of entrapment and labour while keying into and exploiting the geometric language of his Minimalist peers. This presentation runs concurrent with a major survey of the artist's work now open at Zimmerli Art Museum, New Jersey, which travelled from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. His ‘Lynch Fragments', a central part of his practice, currently can be seen in Okwui Enwezor's curated exhibition ‘All the World's Futures' in the 2015 Venice Biennale.

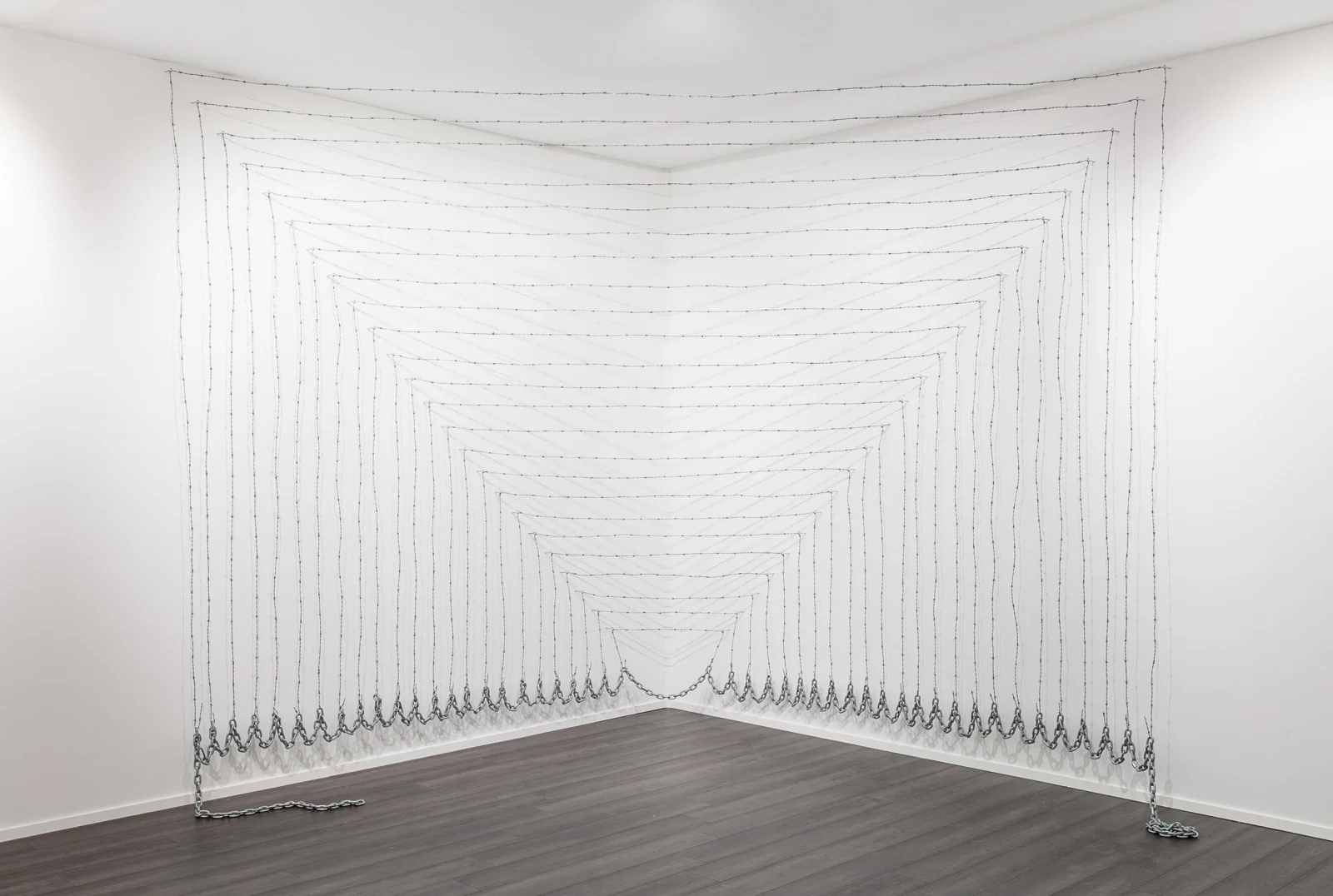

Concentric lines of barbed wire form three lines of a square, each moving further into the corner of a wall. Weighing the twisted, sharp wire downwards is a long chain which extends across its lower edges and forms a fourth line. Viewed in its entirety, the installation presents both a tunnel and a geometric shape. Fixing points on the wall tightly hold and suspend the wire, while the chain heavily drops by gravity's pull. The vibration and movement inherent in the work is curiously emphasised by both the static lines of the wire and the hovering lines of shadows which dramatically fall on the wall. The contrast between the taut wire and loose chains present both tension and suspension, as Edwards creates a spider's web of lines and their shadow counterparts. We see not only linear planes but the spaces in between. We encounter a demarcated space and a physical barrier, yet also a hint of invitation in its tunnelled appearance.

In one respect, the work can be viewed through the lineage of abstract sculpture from Alberto Giacometti through to David Smith and the British post-war artists known as ‘Geometry of Fear'. The exploration of geometry inherent in the work also strongly resonates with Edwards' Minimal and Post-Minimal contemporaries such as Fred Sandback and Sol LeWitt. Yet Edwards goes beyond these simple art historical designations through the physicality and social implications of the material used. The wire glistens enticingly in the light, but bears a menace through both its unavoidable political subtexts and razor sharp edges.

Growing up in Texas, Edwards remembers barbed wire separating farms and fields, and their painful force as a child trying to break through. Originally intended for agriculture, its use in history has since been prevalent in every world war and every social divide. Bringing this into a museum, it forces an alertness that we are unused to in a traditional gallery space. Your movement is destabilised in what is already an elitist cell. Edwards subverted this further in the installations at the Whitney which were titled as a hammock, a curtain and a pyramid, suggesting something familiar and possibly domestic.

This line wire barb thing changing perception

This line wire barb thing changing definition

This line wire barbed thing having connotations

Melvin Edwards, 1970

Other artistic peers had explored the material before but for Edwards there was a forceful politic which was highlighted in his statement for the show, as quoted above. Given the subject matter dealt with by the artist in other works such as the ‘Lynch Fragments', this installation has a profound gravitas relating to American and wider social histories which were still prevalent when this work was conceived. Interestingly, not a single critic commented on the politics of Edwards' message until a year later, when Frank Bowling published his essay ‘It's Not Enough to Say "Black is Beautiful"' addressing this very issue. Bowling praised Edwards for attacking the issue from the inside and subverting the traditional and hallowed white cube. As Edwards himself said, ‘The problem is not the chain; it's how people use it.'

This timely presentation keys into an important period of re-evaluation for an artist who paved the way in forging an art that was unapologetically abstract yet loaded with meaning and resonance.

Installation Views