Overview

Stephen Friedman Gallery presents Reverb, an exhibition bringing together new works by eight leading artists from the Caribbean diaspora: Julien Creuzet, Denzil Forrester, Hulda Guzmán, Suchitra Mattai, Zinzi Minott, Kathia St. Hilaire, Charmaine Watkiss and Alberta Whittle.

Comprising paintings, sculptures, mixed media and sound-based works, Reverb foregrounds the significance of contemporary art from the Caribbean region.

Drawing on the legacy of Life Between Islands at Tate Britain (2021) and Forecast Form at MCA Chicago (2022), the exhibition takes inspiration from Michael Veal’s (Professor of Ethnomusicology at Yale University) description of dub music and its use of reverb as a “sonic metaphor for the condition of diaspora”. Reverb is an effect that occurs when sonic waves bounce off surfaces and create a series of echoes that gradually fade away, making the listener feel like they are physically enveloped by sound. Julian Henriques (Professor at Goldsmiths, University of London) compares the visceral vibrations of Caribbean music to the far-reaching impact of its people and cultures, writing that “the dancehall session serves as a model for diasporic propagation”. Like ripples across the ocean, these reverberations communicate stories of identity, nature and colonialism.

Reverb coincides with a major exhibition by Denzil Forrester at Stephen Friedman Gallery and Andrew Kreps Gallery in New York.

The exhibition is accompanied by a new text written by Rianna Jade Parker (writer, critic and curator, and author of A Brief History of Black British Art (Tate, 2021)).

Stephen Friedman Gallery presents Reverb, an exhibition bringing together new works by eight leading artists from the Caribbean diaspora: Julien Creuzet, Denzil Forrester, Hulda Guzmán, Suchitra Mattai, Zinzi Minott, Kathia St. Hilaire, Charmaine Watkiss and Alberta Whittle.

Like nationalism, the biting phrase ‘diaspora’ can be a powerful stimulus of myths, historical reconstruction and redefinition of a collectiveness. Academically popular keywords and concepts have a way of exhausting their usefulness, but the heart has its own reasons. Caribbean diasporic or transnational movements are more than just ‘place to place’. Under the critical authority of Stuart Hall (Professor of Sociology at Open University), the Caribbean can be understood as the only group that is twice diasporised and “constantly producing and reproducing itself”. In his 1995 essay Negotiating Caribbean Identities for the New Left Review, Hall pronounced: “the Caribbean is the first, the original and the purest diaspora”. But has the theory, practice and purpose between it all been affirmed yet?

Rianna Jade Parker (writer, critic and curator, and author of A Brief History of Black British Art (Tate, 2021))

Julien Creuzet

Four anatomic-configurations by French-Martinican Julien Creuzet are substantially weighted by an assemblage of found materials such as pearls, steel and plastic, implicative of the amalgamating process unique to the Caribbean. Dans nos yeux, words come from far away, from my ancestral memory, astral, sky, I’m not alone on the way anymore (rouge et jaune) (2020–2024) features a humanoid figure with a protruding chest, leading the charge, roofed by a tri-coloured wide-palmed leaf. For Creuzet the body’s positioning is a construction for “experiential agency and self-determination”, a theoretical nod to Martinican writer Édouard Glissant and his theory of relatedness and creolisation.

The Caribbean transatlantic triangular world was formed through mercantilism, the slave trade and settler colonialism of European empires. It is not possible to separate the concept of diaspora from the experience of economic and political migration, asylum seekers and refugees, or even of the transient traveller.

Denzil Forrester

The British-Caribbean diaspora has well defined itself in the last 70 years since mass migration upon-invitation. Denzil Forrester is still able to recall and directly reference old sketches and his first-hand accounts of dub clubs popularised in 1970s and 80s London, built and sustained by the early Windrush Generation. In honour of the late London-based DJ Jah Shaka, Forrester’s Zulu Chant (2023–2024) is a yellow, orange and purple toned mise-en-scène of the cultural intervention of Reggae in Britain, revellers and revolutionaries with sting and style.

Diasporic consciousness nearly always involves an aspiration of establishing an original homeland and a degree of commitment to an eventual turn, or simply a referent of spiritual or emotional renewal. To be truly fruitful the descriptive, evaluative or explanatory powers of a diaspora must expand beyond recognition of a lineal heritage — these finer contours are more alluring.

Rianna Jade Parker

Hulda Guzmán

Hulda Guzmán’s fantastical panorama of her immediate surroundings at her studio in the countryside of the Dominican Republic, A little tune-up (2024), is a tropical surrealist demonstration of how to rebalance, recuperate and recommit. In this world, Guzmán has conceived an equilibrium of colour and space for plant life, domestic and roaming animals, living and transcendental spirits, otherwise known as family. She remarks: “I hope to understand the delicate balance between man, wildlife and the environment and to transmit a perspective of synergy; to portray trees and plants as glorified, deified, as to inspire worship, respect and reverence upon Nature”.

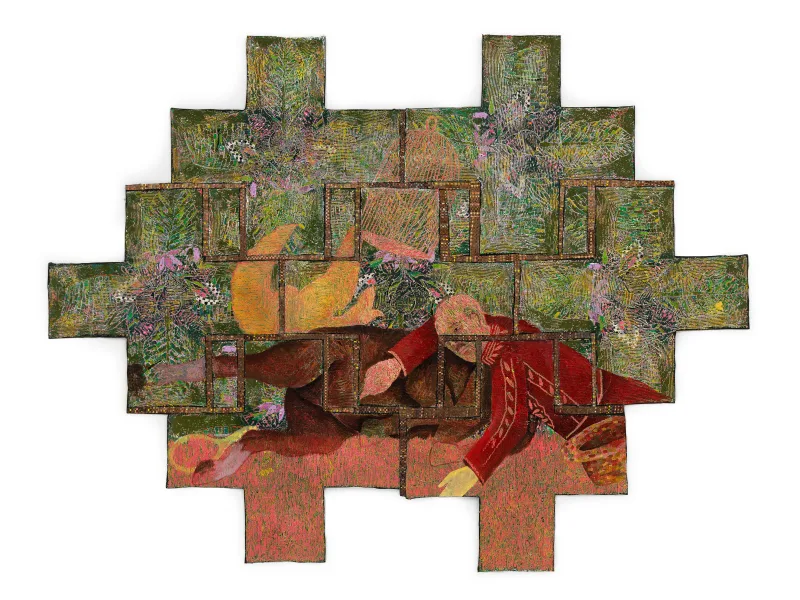

Suchitra Mattai

Suchitra Mattai’s multi-disciplinary practice draws on her South Asian heritage and her ancestors’ migration from India to British Guiana on South America’s north Atlantic coast — now Guyana — as indentured labourers in the 19th century. The artist’s work incorporates materials and domestic craft techniques typically associated with female labour that have been passed down through generations. Mattai’s imposing new tapestry set free combines woven vintage saris with beaded fringing and shimmering gold tassels. A female figure floats in the centre of the composition as if drifting through time and space, alluding to the sense of displacement Mattai relates to the experience of Indo-Caribbean immigrants.

In her delicate and sophisticated tapestry, transference (2024), Guyanese Suchitra Mattai sets a scene of Indo-Caribbean women's agency and actualisation. A brown-skinned woman dances in the centre of the surface framed by a medley of ghungroo bells, traditionally used to emphasise complex footwork and dance skill. Privileged white Europeans surround her, but their faces are blurred through horizontal over layering of blue and yellow thread. Centuries-long Indo-Caribbean heritages were transferred to Mattai; it was her grandmothers who taught her fine embroidery skills and her mother shared other cultural fibre materials, such as the sari woven into the work.

Zinzi Minott

Zinzi Minott was born in 1986 in Manchester and in 1992 moved to London, UK, where she still lives and works.

Minott is Trinity Laban Conservatoire alumni and was the first artist trained in dance to be an Artist in Residence at both Serpentine Gallery, London (2018) and Tate, London (2017).

Minott’s sound work WATASOUND (2024) utilises public and personal archives to reference political speeches, carnivals, thrashing water and other field recordings of conversational Jamaican Patois in social settings. Her sonic passage is the most sensitive to the concept of reverberations that uniquely require a sense of hearing and touch. Rhythmic dub and bass, Rastafari chanting and contemporary Dancehall are blended with street talk and alighting political speeches with calls for reparations. Working predominantly in sound and performance, Zinzi’s practice loops lived bodily experience with fiction and fact despite afflictions the archive can weld.

Rianna Jade Parker

Excerpt from 'WATASOUND' (2024)

Kathia St. Hilaire

Inspired by the writings of Rita Dove and René Philoctète, the figures depicted in St. Hilaire’s multi-layered new works reference the Parsley Massacre of 1937, when Dominican soldiers were ordered by military dictator Rafael Trujillo to kill Haitians living near the Dominican-Haitian border. The paintings feature motifs including banana leaves, avocados and flowers – all inspired by her parents’ garden. St. Hilaire uses them as ‘offerings’ to reference the Haitian Vodou spirit Azaka, the spirit of agriculture and peasant farmers, and honour the Haitians and Dominicans living in the border town murdered by Trujillo.

In Azaka (2024), she immortalises one victim of the massacre; the tropical bird flies above the head of a blue-collared young man, skin emboldened with the same burning gold hue as the parrot.

Rianna Jade Parker

Charmaine Watkiss

This ongoing body of work explores the indigenous knowledge that West African women brought to the Caribbean, focusing on the traditional healing properties of plants passed down from their ancestors. Her new drawings in Reverb are underpinned by research undertaken at The British Museum, looking into Sir Hans Sloane’s (1660–1753) documentation of plants during his time as a physician to slave plantations in Jamaica. Watkiss’ figures, confident in their stature and based on the artist’s likeness, manifest the wisdom and resilience she associates with Caribbean women.

Through sustained botanical research, Charmaine Watkiss continues to extend her women-dominated Plant Warrior series with five new drawings. An African-Caribbean woman, based on the artist’s likeness, is perfectly poised for her portrait in The Warrior’s presence is safeguarded for generations to come (2024). She is characterised by the anchovy pear tree that is indigenous to Jamaica and produces fruit sweetly similar to mangoes. With her haired braided backwards, she is framed by a collar made up of large green leaves seemingly growing through and around her body and neck, where more adornments rest. I warmly recognise the Abeng resting on her leg. A Twi word translating to ‘whistle’, the Abeng is a cow-horn instrument that was used by Jamaican Maroons for ceremony and crucial communication in opposition to British colonialists.

Rianna Jade Parker

Alberta Whittle

Alberta Whittle’s sculptural installation A knock, a kick and we grapevine (2024) centralises a slanted threshold on a gradient coloured frame and grounded by sacks of sandbags. At this angle, a bronze-casted foot rests on the lower half on a repurposed white door decorated with fluorescent pink glass panels, typical in the Anglophone Caribbean. This foot could belong to an impatient visitor or a playful child, both wanting access through this foyer to a new potential.

Two new textile works stretched on vibrantly painted frames – Beneath the waves, we shapeshift (before I was a shipworm) and Beneath the waves, we shapeshift (before I was a hermit) – are featured in the exhibition. Resting on wheels, these sculptures gesture toward performance or movement. Door-like in structure, Whittle envisages them as portals or passageways to an alternative future by depicting various forms of resistance. Both reference the myth of Drexciya – an Afrofuturist story about an underwater empire created by the unborn children of enslaved African women – by depicting an interspecies relationship between a woman and a hermit crab.

Generalisations about the transnational characteristics and caricatures of Caribbean life are only mildly helpful as a guide to the uninitiated, to our differences and similarities, divergences and parallels that begin to emerge and overlap, as they must. One can also trace the convergences and divergences through the literary and intellectual formulations of: C.L.R James (1901–1989), Amy Ashwood (1897–1969) and Marcus Garvey (1887–1940), Suzanne (1915–1966) and Aimé Césaire (1913–2008), Claudia Jones (1915–1964), Arturo Schomburg (1874–1938), Elsa Goveia (1925–1980), Kamau Brathwaite (1930–2020) and the still living Sylvia Wynter (b. 1928).

Rianna Jade Parker